Abdul and Rabia (names changed) arrived on Lesbos with their three children in summer 2019 to seek refuge from the war in Afghanistan. It took two years until they were granted refugee status and received their documents. During this period, they have lived in all four camps on the island: first Moria, then Pikpa, then Kara Tepe, and finally the new camp “Moria 2” – or Mavrovouni, which is how authorities call it.

Tents in the „Olive Grove“, the „wild“ camp next to Moria

Family houses in Pikpa

Container Camp Kara Tepe

Moria 2 / Mavrovouni / „new Kara Tepe“

Abdul´s 42nd birthday was a very special day. After one year, eleven months and seventeen days, he and his family finally received their documents as recognized refugees. “It was my best birthday present”, he laughs. They have now three days remaining until they leave to the Greek mainland – something for which they have been waiting for such a long time. During the three hours in which they are allowed to leave the camp, one of their ways leads them to the office of Lesbos Solidarity: “The reason why we are coming today is to say good-bye to everyone. We very much appreciate what you have done for us”, says Rabia. As they are going through the rooms to greet everyone for a last time, one can sense the relief that they are finally able to leave the island.

We decided to leave, so that our children can live in safety. So, that my husband can go to work and I know that he will come back in the evening. In Afghanistan, I never knew if he will return.

Abdul and Rabia belong to the ethnic minority of Hazara in Afghanistan and fled Kabul with their 16-year-old and 9-year-old sons and their 12-year-old daughter. “There were mainly two reasons why we fled”, says Rabia. “First, there was no safety. Where we were living, there was fighting almost every day. Once, I experienced a blast in our direct vicinity, and incident which still gives me nightmares. And second, we were receiving death threats. We decided to leave, so that our children can live in safety. So, that my husband can go to work and I know that he will come back in the evening. In Afghanistan, I never knew if he will return”. And she adds: “I wanted to live in a country where I have freedom. In Afghanistan, women don´t have any rights. I want to study. I want to become a doctor. This was not possible in Afghanistan. I want to be able to go to work, to study, to drive a car, to ride a bike, to go for a coffee. I want to live in a place where there is freedom”.

Name of the Camp: Moria

Site: former military camp

Operated by: EU, Greece

Max. occupancy: 22.000 (in 2020)

Abdul knows all the dates of arrivals, relocations and departures by heart: “We arrived on Lesbos on 15 June 2019, and we were straight sent to Moria”, he explains. At that time, the EU hotspot was already overcrowded with more than 5.000 people in a facility with a capacity of just 3.000. The actual camp was full – for years, new arrivals had to set up their tents in the olive groves around the former military site. And the situation became even worse. When they were finally able to leave Moria in December 2019, the number of inhabitants of the camp had skyrocketed to more than 18.000.

There were 14 people in that tent. When we were sleeping, we couldn´t even turn around, because of how cramped it was.

“We had to live in a small four meters long tent in the forest, together with two other families”, describes Abdul. “There were 14 people in that tent. When we were sleeping, we couldn´t even turn around, because of how cramped it was”. There was no water and electricity, and the weather was getting colder and colder. “The first months were a very hard time” says Rabia. “We didn´t have money anymore, because we had already tried 14 times to cross the sea to Lesbos. And we did not get any financial aid”. Just after three months they received 50 euros a month per person from UNHCR, and for Abdul a bit more.

The days in the camp consisted of waiting. “Often, I had to stay in the food line for breakfast from 6 to 9 in the morning”, says Abdul. “In the end, I would get one bottle of water and a small cake per person. From around 12 to 5, I was standing in the food line for lunch – for example, boiled eggs with tomatoes – and from 5 to 9 for dinner. In the beginning, there were around 500 people in our food line, but in the end, it was more than 3.000. Sometimes we didn´t receive anything, because they ran out of food. There were times when we got lunch only twice per week”.

Rabia especially recounts the lack of safety in the camp. She always feared for her children. “I was even taking them with me in the line for the toilet. Every time I went there, there were already 20 to 30 people queuing up. One cannot even describe how dirty the toilets were inside – I could not even put my foot on the ground”. It was even more difficult to get into the showers. Rabia remembers that one day she left at 11 in the morning to take a shower, and came back at 5 in the evening. Even in December, the showers did not have hot water. Sometimes, there were sudden water cuts. Rabia remembers that she once stood under the shower, covered with soap, when the water stopped. The children spent most day in the tent. “In Moria, they lost a lot of weight”.

They were throwing stones at the tents. I remember how once a stone hit our tent. We were scared every night.

But the worst thing were the nights. “Women could not even step out of the tents at night”, explains Rabia. “There were people who were drunk and who attacked women. And there were fights between different groups in the camps. They were throwing stones at the tents. I remember how once a stone hit our tent. We were scared every night”. Rabia often had nightmares, which invoked memories from the war in Afghanistan. At some point, people of other ethnic groups threatened to set the tents in the area on fire, where Abdul and Rabia lived together with other Hazara and Arab families. The men organized a watch group during the night. Abdul also stayed awake to protect the tents. “The situation was hard”, he says. “During this time in Moria, all my hair turned white. I would never have expected this in Europe”.

Name of the camp: Pikpa

Site: former holiday camp for children

Operated by: Lesvos Solidarity

Capacity: 120

Abdul was visiting UNHCR and other organizations again and again to request to be transferred to different accommodation. “My wife had mental health problems. She had nightmares. We needed a place for ourselves”. But it took half a year until they were finally offered a place in Pikpa camp. They moved there on December 7th 2019.

When I entered the gate of Pikpa, I felt like I was passing from hell to heaven.

“When I entered the gate of Pikpa, I felt like I was passing from hell to heaven” says Rabia. “There were beautiful houses, no tents or isoboxes. The volunteers and staff members were waiting for us and said: Welcome to Pikpa! It was December and there was hot water. The children were so happy! They immediately jumped into the shower. There was electricity, good food and a playground for the children. But most important, there was safety. I could sleep at night. There were no knives, no fights, no loud noise. No police, no gatekeepers. For the first time, I felt safe – as in the belly of my mother”.

The parents could see how their children found their way back into life. They started to play, gained weight, they participated in a drawing class and a music class in Pikpa. “There were celebrations and dancing”, says Rabia. “I remember when Knut, one of the volunteers, baked a big cake for everyone. There were even swimming classes for the children at the sea. We attended English and Greek classes. There was a nurse where we could go and the children were enrolled in a public school – just before it was closed due to corona. Twice per week, we received a food box for cooking. Everything was good”. When Moria burned down in September, the residents of Pikpa started to cook meals for the people who were living on the streets for several days.

The house of the family in Pikpa

Rabia cooking for the homeless asylum seekers after the fire in Moria

But shortly after the fire, the Greek authorities declared they would close Pikpa. “We saw it in the newspaper. We were shocked“, says Abdul. “We were scared they would throw us into the new camp. “ Pikpa was the centre of attention for some weeks. “Many journalists came. I also gave an interview – I think the journalist was from Canada“, says Rabia. “The people of Pikpa worked hard and tried to save us. They started a campaign. We still have the t-shirts with the writing ´Save Pikpa – Save Dignity`. But all that could not save Pikpa. At first, the police came on 29 October and tried to kick us out. But the children were at school, some people were in town. Efi from Lesvos Solidarity came and talked to the police, and finally they left again.“

They said: Just take your stuff. You have ten minutes.

But they came back the other day. “It was around 6.30 in the morning, at first sunlight, when I heard the noise of boots marching on the ground “, recounts Rabia. “The children were sleeping. I opened the door to see what was going on, and I saw people in white body suits as a protection against corona. There were four or five such people dressed in white, standing in front of our door, and behind them there were eight or nine police officers. They were not polite at all. They said: ´Just take your stuff. You have ten minutes.´ When I woke up my children, they got scared and started to scream. I calmed them down and asked the policemen to go some steps back. But they just said: ´This is not our problem. You have ten minutes. Otherwise, we have permission to enter the house. ` They didn´t even let us close the door to arrange our things.“

“They came after us as if we were criminals “, adds Abdul. “I have never seen such police forces before, with shields and everything. In front of us was an Arab family that was completely encircled by policemen. They even stood all the way along the street in front of the camp. I was thinking to myself: We must be the most dangerous people. But in fact, we were the most vulnerable. I´m wondering what they’d think of us that they sent us this police.“

The families could not even say goodbye. “The volunteers were kept 500 metres away from us. We waved goodbye to them through the windows of the busses”, says Rabia. “The children were all crying. I had felt that I had moved from hell to heaven when I came, and now they took heaven away from us”.

Name of the camp: Kara Tepe

Site: former bicycle training centre for children

Operated by: Municipality of Mytilene

Max. capacity: 1.300

The families from Pikpa were brought to Kara Tepe, a camp suitable for vulnerable families, managed by the municipality of Mytilene. “It was better than Moria, but worse than Pikpa“, says Abdul. The family spent a full winter in an 18 metres long isobox. “The toilets were fine, the showers had hot water sometimes. The problem was that we had electricity only some hours per day, and the heaters did not work without power. During the night, it was very cold. We wore socks, gloves, scarfs, used sleeping bags and several blankets. But nevertheless, sometimes I woke up because of the cold. The children coughed and had a cold all the time”. Many times, Abdul went to the managers of the camp to complain. “Once, all us Pikpa families were gathered, went to the office and told them: ´We need electricity.` But they just said to us: ´If you are not happy here, you can go to the new camp.`“

The children had to stay in the camp for five months without a break. They could never go outside.

It was the winter of the second corona wave, and the lockdown in Greece began at the same time as the family was moved to Kara Tepe. “We were just allowed to leave the camp twice per week”, says Abdul. “One person per family per week was allowed to go to the Lidl supermarket nearby, and one person per family per week was allowed to go to town. The children had to stay in the camp for five months without a break. They could never go outside”.

On 29 April, the authorities closed down Kara Tepe, as well – the last camp suited for vulnerable persons on Lesbos. “The police came at 5 o´clock in the morning. I don´t understand why they had to move us so early in the morning”, describes Rabia. “But this time, they had announced everything the day before. So, for this second eviction, I was not shocked. I woke up the children at 4, and we prepared”. Again, special police forces were sent to remove the families from the camp. “It was the same cars and the same policemen as in Pikpa”, says Abdul. “Everything was the same. Only one thing had changed: They did not yell at us. And we had some time to prepare”.

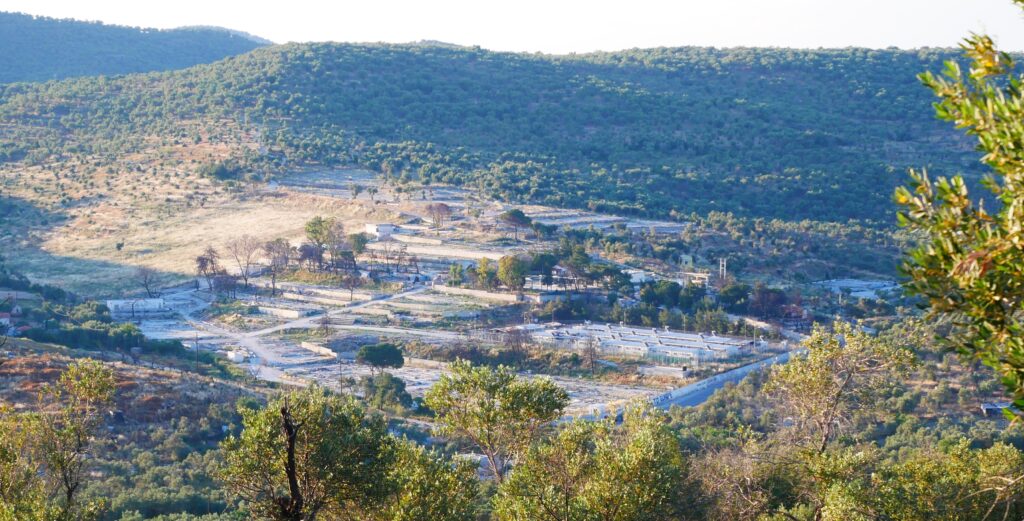

Name of the camp: Mavrovouni, „Moria 2“, „new Kara Tepe“

Site: former military shooting range

Operated by: EU, Greece

Max. occupancy: 9.500 (in 2020)

The families from Pikpa camp, along with all vulnerable asylum seekers in Kara Tepe, were brought to the new “Registration and Identification Centre” next to the sea, which the Greek military had hastily erected on the site of a former shooting range after the fire in Moria. Just like that, the Greek authorities broke their promise given six months before then, that the vulnerable asylum seekers from Pikpa would not be brought to the new camp.

Moria 2 / Mavovrouni / „new Kara Tepe“

During the winter, thousands of people had spent terrible months there, living in overcrowded tents without privacy. Sanitary facilities were never appropriate. In the beginning, there were no showers at all, for months people had to wash themselves and their clothes in the sea. Cold weather, strong winds and repeated floods made the conditions in the camp unbearable during the winter. A strict lockdown was imposed, which lasted even after the restrictions outside the camp were lifted and tourists from all over Europe were allowed to travel to Lesbos and move freely on the island again.

“The new camp is bad”, says Abdul. “Very bad. In some ways, it is the worst. Worse than Moria.“ Again, the family had to live in a small tent, together with another family. While they had been able to go out from Moria, they were now practically locked up in the new camp. “We are just allowed to leave the camp for three hours a week”, says Abdul. While in Moria, at least trees offered some shade, in the new camp the people were exposed to the sun, with a lot of dust in the air. “The children are almost always in the tent. For them, there´s nothing to do in the camp”, says Rabia. Some things were better than in Moria, especially safety, and the food lines were also better organised. “But I cannot even describe the bad quality of the food”, says Rabia. “Sometimes, you cannot even eat it. Once, we found white bugs in the rations, and even made a video to prove it”.

On June 5th, at 6am in the morning, Abdul, Rabia and their children finally enter the ferry to the Greek mainland. As recognized refugees, they are expected to look for work and accommodation themselves – an almost impossible task for the big majority of recognised refugees and asylum seekers in Greece. Many of them end up at the streets in big cities, several try to leave Greece to find shelter in other European countries. An uncertain future awaits them. But on that very morning under a clear sky in the port of Mytilene, all that counts is: They finally leave this hard time behind them – all these 718 days in which Europe has restrained them in different camps on Lesbos.